Leaching of metals from household taps—new report

6 July 2020

A newly released scientific report sheds further light on leaching of metals from household taps in New Zealand.

A newly released scientific report sheds further light on leaching of metals from household taps in New Zealand.

For some time now, Master Plumbers has been highlighting the risks to human health of lead leaching from substandard tapware on sale in New Zealand.

In 2018, Master Plumbers commissioned an independent test of five tapware products sold in New Zealand, which found the level of lead leaching from one product purchased online to be 70 per cent higher than the allowable limit.

The Master Plumbers' study has now been extended through a new joint project, led by Massey University and the Centre for Integrated Biowaste Research (CIBR). The aim of this new study was to quantify the leaching of lead, copper, zinc, nickel and chromium from a range of tap materials commonly found in New Zealand after a stagnation period of between one and 14 days.

For the test, Methven kitchen and bathroom taps certified to tapware Standard AS/NZS 3718 were compared with kitchen and basin taps purchased online and assumed to be non-certified.

Trace metal concentration limits given in the New Zealand Drinking-water Standards were used as a benchmark for assessing potential health significance of metals leaching from the tapware—of which lead is of the most concern to human health, and zinc and copper to the environment.

Study findings

The 2020 study report, entitled Something in the Water: Investigating the Leaching of Metals from Household Taps, found that household taps are a significant source of drinking water trace metal contamination. It states that the obvious route to eliminate these unnecessary sources would be through the New Zealand Building Code, which doesn't currently specify AS/NZS 3718.

Although the Ministry of Health acknowledges that metals leach from plumbing pipes and fittings in people's homes, the Drinking-water Standards are not legally enforceable, and the Ministry doesn't monitor them. Instead it recommends the public 'flush' a small amount of water from their taps before drawing water for consumption.

However, as the study report notes, whilst people can flush water from their taps before drinking, the leached metals will subsequently go to the wastewater treatment plant and eventually into the wider environment.

The report's authors conclude that buyers need to understand the importance of choosing good quality tapware. "Anecdotal evidence from the plumbing industry suggests that poor quality tapware can sometimes be stamped with AS/NZS 3718:2005 even though it does not comply. This suggests that some form of monitoring may also be required in New Zealand, similar to requirements that exist in Australia."

Master Plumbers, Gasfitters and Drainlayers NZ CEO Greg Wallace agrees. "Master Plumbers has been lobbying MBIE for a mandatory third-party verification scheme similar to WaterMark," he says. "This report back up our concerns that plumbing products are available in the New Zealand supply chain that put public health at risk through lead leaching into drinking water."

Conducting the test

For the test, three identical kitchen and three identical bathroom taps, all certified to tapware Standard AS/NZS 3718, were compared with three identical kitchen and three identical basin taps purchased online, which were assumed to be non-certified.

AS/NZS 3718 is not cited in the Building Code, so compliance is voluntary, but a number of reputable tapware suppliers in New Zealand choose to do so.

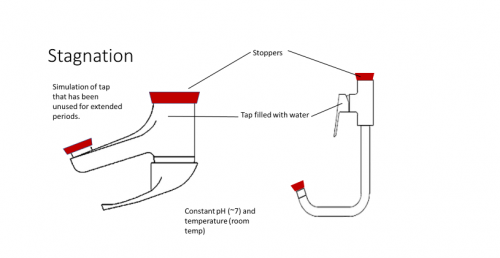

All tested taps were rinsed to flush out any manufacturing process residues, then filled with double distilled pH 7 water, stoppered and left to stagnate (see diagram below). The water was agitated before sampling, with samples taken at 24, 48 and 72 hours, then five and 14 days to measure metal concentrations. This photograph shows the certified tap set-up.

Test results

The test results show that non-certified taps in general leach higher concentration of metals. "In some cases, leaching of metals can be far in excess of drinking water limits," notes the report. "For example, the non-certified kitchen tap leached zinc to concentrations 7.5 times the limit after one day of stagnation. Zinc concentrations are significant relative to potential accumulation in sewage effluent or biosolids."

|

The non-certified basin tap performed worst of the four taps, with the greatest leaching of lead throughout. However, levels remained below the maximum allowable limit in the drinking water standard. |

|

Both the certified basin and non-certified kitchen taps leached zinc in excess of the guideline limit in the drinking water standards. The non-certified tap in particular produced an initial concentration 7.5 times over the limit. |

|

The certified basin tap leached nickel above the threshold limit and in some cases nearly double the limit. The leaching remained consistent from day one onwards, suggesting it was a 'first flush' that would reduce over time under typical use. By contrast, the non-certified basin tap initially showed low levels but these increased rapidly throughout the experiment, reaching 22 times the drinking water standard by day 14. |

|

Only the non-certified kitchen tap exceeded drinking water limits for chromium, which increased gradually before reducing by day 14. |

|

Copper concentrations were all below the drinking water standard limit throughout the 14-day test. |

Lead of greatest concern

Lead is one of few substances known to cause direct health impacts through drinking water, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Lead is one of few substances known to cause direct health impacts through drinking water, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Several countries have rules in place for products in contact with drinking water and in 2018 the European Commission proposed lowering the lead limit to 5 μg/dL, as it is already in countries such as Sweden and Denmark. The New Zealand Drinking water Standards currently recommend a limit of 10 μg/dL.

The lead concentrations in water from all four taps tested in the study remained below the New Zealand and WHO drinking water standards. However, a significant difference in overall leaching was observed between taps, with the non-certified basin tap consistently higher for lead than the other three.

"Although concentrations were below limits, it may be possible for lead levels to exceed 10 μg/dL within 42 days if leaching continued to increase at the observed rate," the report noted.

Do proposals for change go far enough?

A Bill currently before Parliament proposes "significant" changes to the regulation of all building product in New Zealand, according to John Sneyd, General Manager Building Systems Performance at MBIE.

"The Building (Building Products and Methods, Modular Components, and Other Matters) Amendment Bill includes the requirement for manufacturers and suppliers to make a minimum level of information publicly available about the building products they sell," he says.

"It also includes amendments that will significantly strengthen New Zealand's product certification scheme, CodeMark, to provide higher levels of assurance that products will comply with the Building Code. MBIE considers that these changes together will provide similar levels of assurance for plumbing products in New Zealand as the WaterMark scheme does in Australia."

The Bill has now been referred to a select committee, with Master Plumbers having made a submission prior to the consultation closing date of 10 July. "It is worth noting that many of the details of the scheme will be contained in regulations, which MBIE intends to begin public consultation on later this year," says Sneyd.

"Matters such as product testing, enforcement and auditing were discussed in some detail during consultation on policy proposals for the Bill, and are matters which will be under active consideration when the detailed policy work on the regulations begins."

Master Plumbers CEO Greg Wallace says Master Plumbers is pleased that the Government is addressing the issue but says testing is the only way to make a product quality assurance scheme truly effective.

"At least 15-20% of products each year would need to be audited," he says. "Without such auditing, how can it be sure that suppliers are actually meeting the minimum standards?"

MBIE must also enforce compliance, with penalties for suppliers whose products fail such audits, he says.

"Master Plumbers spends up to $20,000 a year reviewing and developing plumbing Standards for MBIE, but if these Standards are not policed, we wonder what real value they have," says Wallace. "In our view, the Australian WaterMark system is the gold standard for plumbing product supplier compliance.

"It is a far more comprehensive and robust approach because all products are required to have third party testing and verification before being sold.

"By citing tapware Standard AS/NZS 3718:2005 in the New Zealand Building Code, it would become mandatory for all tapware suppliers to comply."

Did you know?

- Tapware Standard AS/NZS 3718: 2005 is not currently embedded in the Building Code.

- AS/NZS 3718 requires that copper alloy tapware parts in contact with water are made of dezincification resistant brass (DZR), certified to Australian Standard AS 2345.

- Many reputable tapware companies in New Zealand conform voluntarily to AS/NS 3718.

- Taps sold online don't necessarily conform to any standard.

This article first appeared in the June-July 2020 edition of NZ Plumber magazine.